I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the content in Young Adult fiction, and what is, or isn’t considered ‘suitable’. In fact, I’ve thought about it a lot in the past as well, but never got around to committing my thoughts to paper. So here they are.

I have so many questions in my head around this issue, for example, do our young people need to be exposed to material that might be described as ‘upsetting’ or even ‘disturbing’? To what extent does historical and cultural setting influence a reader’s responses? And how does contemporary fiction compare to more classical fiction in terms of issues, acceptability and language?

The main ‘problem’ some people have with my books, I think, is that they are contemporary. Being set in the here and now seems to make the issues raised more acute. There isn’t the distance of time, or culture, or language. The issues faced by my characters – physical abuse, underage sex, teenage pregnancy, drug use, gangs, knife and gun crime etc – are very close to us – whether we like it or not. And it seems that some people just don’t like it. I can see why we don’t like to think about these things happening to our young people, what I can’t understand, is why some people don’t like to even acknowledge that these things happen.

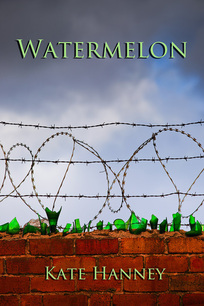

One could argue that our young people don’t need to know about such issues, even if they are real. But why not? Obviously, I’m not going to be reading WATERMELON to my six year old, but in a few years’ time, I will absolutely be putting that book in front of her. It’s great that my kids read about middle-class girls with ponies, about youngsters who go off on adventures to exotic places, and about kids who live in warm, safe homes with caring parents and a Labrador. But equally, I want them to know that not all kids have this. I want them to know that some kids grow up in abusive households, some kids go hungry, some kids have no-one to hug them at night. It’s important. If they don’t know, how can they ever develop any appreciation of how our society works?

When they see a homeless teenager begging on the street, what do I want them to think? That the person’s there by choice? That they’re enjoying the experience? That they’re loving the freedom of being addicted to drugs, turning to prostitution, being alone, hungry, begging for a few quid?

No, I don’t. I want them to think, how did that kid end up there? What must their life have been like before, for this existence to be preferable? And that also goes for the kids who join gangs, kids in care, kids who end-up in Young Offending Institutes. Yes, I know some young people make some awful choices and do some awful things, but what influences and experience have led them to that point?

So, for teenagers who don’t go through these experiences, I believe they need to know it happens. For teenagers who do, they need to know it’s not just them. They need to know not everyone has the hugs or the Labrador or the ponies. Not every other child is loved, and fed and kept safe at night; they aren’t on their own.

Of course, kids having a difficult time is nothing new in literature. Oliver Twist immediately springs to mind. Orphaned boy, runs away from cruel and abusive carers, joins a criminal ‘gang’, tries to make the right choices, gets dragged back into a word of crime, commits thefts, witnesses violence and murder. Commonly taught in primary schools.

Let’s consider some of the texts listed on the GCSE syllabus: Of Mice and Men, Romeo and Juliet, Tsotsi, To Kill a Mocking Bird. Issues raised: racism, teenage sex, poverty, mugging, knife-crime, murder, gangs, kidnapping, rape, violence, enforced marriage.

No one bats an eyelid.

And what do they have in common? They aren’t set in the here and now. We are separated from them by either time or culture. And because these issues aren’t happening on our doorstep, we are encouraged, compelled even by the exam boards, to read and study these texts with our young people.

Contemporary, issue based novels however, often solicit a very different response. For some adults, they seem to represent a more threatening, damaging force. There is a fear that our young people will be corrupted, that they will enter into the dark, dangerous worlds that these novels present. But this is how I see it: kids who are already involved in these worlds know all about it anyway, and these novels might just help them to feel less alone, possibly identify a way out and make some positive choices. Kids who aren’t involved, have avoided these situations for a reason; they have other influences in their life that keep them safe. And these influences aren’t going to disappear simply because they read a book.

For me, there is very little that can’t be tackled in fiction for young adults, as long as it’s presented in an honest and sensitive and responsible way. There is nothing glamorous about the issues I deal with – even if the characters, just like the young people involved, think so initially – and I hope I show this unreservedly. But what I also hope I show, is how these youngsters came to be who they are and why they do what they do. And ultimately, what I want my readers to consider, is if they’d had that life, would they be any different?

I have so many questions in my head around this issue, for example, do our young people need to be exposed to material that might be described as ‘upsetting’ or even ‘disturbing’? To what extent does historical and cultural setting influence a reader’s responses? And how does contemporary fiction compare to more classical fiction in terms of issues, acceptability and language?

The main ‘problem’ some people have with my books, I think, is that they are contemporary. Being set in the here and now seems to make the issues raised more acute. There isn’t the distance of time, or culture, or language. The issues faced by my characters – physical abuse, underage sex, teenage pregnancy, drug use, gangs, knife and gun crime etc – are very close to us – whether we like it or not. And it seems that some people just don’t like it. I can see why we don’t like to think about these things happening to our young people, what I can’t understand, is why some people don’t like to even acknowledge that these things happen.

One could argue that our young people don’t need to know about such issues, even if they are real. But why not? Obviously, I’m not going to be reading WATERMELON to my six year old, but in a few years’ time, I will absolutely be putting that book in front of her. It’s great that my kids read about middle-class girls with ponies, about youngsters who go off on adventures to exotic places, and about kids who live in warm, safe homes with caring parents and a Labrador. But equally, I want them to know that not all kids have this. I want them to know that some kids grow up in abusive households, some kids go hungry, some kids have no-one to hug them at night. It’s important. If they don’t know, how can they ever develop any appreciation of how our society works?

When they see a homeless teenager begging on the street, what do I want them to think? That the person’s there by choice? That they’re enjoying the experience? That they’re loving the freedom of being addicted to drugs, turning to prostitution, being alone, hungry, begging for a few quid?

No, I don’t. I want them to think, how did that kid end up there? What must their life have been like before, for this existence to be preferable? And that also goes for the kids who join gangs, kids in care, kids who end-up in Young Offending Institutes. Yes, I know some young people make some awful choices and do some awful things, but what influences and experience have led them to that point?

So, for teenagers who don’t go through these experiences, I believe they need to know it happens. For teenagers who do, they need to know it’s not just them. They need to know not everyone has the hugs or the Labrador or the ponies. Not every other child is loved, and fed and kept safe at night; they aren’t on their own.

Of course, kids having a difficult time is nothing new in literature. Oliver Twist immediately springs to mind. Orphaned boy, runs away from cruel and abusive carers, joins a criminal ‘gang’, tries to make the right choices, gets dragged back into a word of crime, commits thefts, witnesses violence and murder. Commonly taught in primary schools.

Let’s consider some of the texts listed on the GCSE syllabus: Of Mice and Men, Romeo and Juliet, Tsotsi, To Kill a Mocking Bird. Issues raised: racism, teenage sex, poverty, mugging, knife-crime, murder, gangs, kidnapping, rape, violence, enforced marriage.

No one bats an eyelid.

And what do they have in common? They aren’t set in the here and now. We are separated from them by either time or culture. And because these issues aren’t happening on our doorstep, we are encouraged, compelled even by the exam boards, to read and study these texts with our young people.

Contemporary, issue based novels however, often solicit a very different response. For some adults, they seem to represent a more threatening, damaging force. There is a fear that our young people will be corrupted, that they will enter into the dark, dangerous worlds that these novels present. But this is how I see it: kids who are already involved in these worlds know all about it anyway, and these novels might just help them to feel less alone, possibly identify a way out and make some positive choices. Kids who aren’t involved, have avoided these situations for a reason; they have other influences in their life that keep them safe. And these influences aren’t going to disappear simply because they read a book.

For me, there is very little that can’t be tackled in fiction for young adults, as long as it’s presented in an honest and sensitive and responsible way. There is nothing glamorous about the issues I deal with – even if the characters, just like the young people involved, think so initially – and I hope I show this unreservedly. But what I also hope I show, is how these youngsters came to be who they are and why they do what they do. And ultimately, what I want my readers to consider, is if they’d had that life, would they be any different?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed